When we see the sturdy arm of a heavy excavator, the powerful crankshaft of a giant ship, or the high-speed gears in a wind turbine, we might not realize that the metals used to manufacture these critical components were initially a delicate balance between strength and toughness. Tempering heat treatment is precisely this art of balance, an industrial magic that transforms forgings into a perfect material that combines strength and flexibility.

I. What are Forgings? Why is Tempering Necessary?

1. What Are Forgings?

First, let’s get to know the main character—forgings.

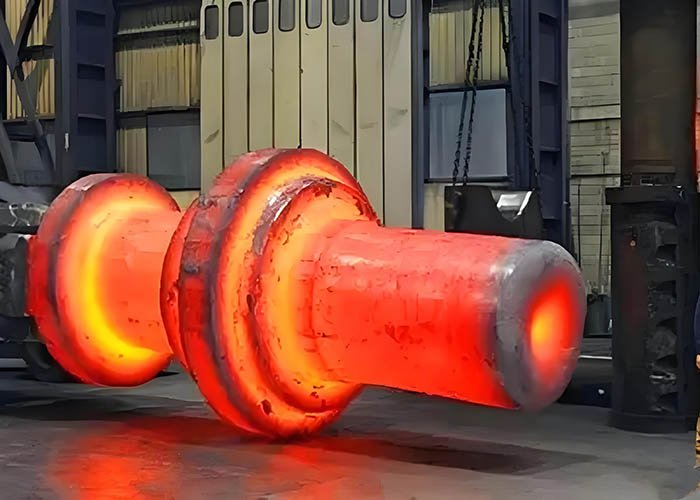

Forgings are made by heating metal billets and then hammering and pressing them with a forging hammer or press, causing plastic deformation to ultimately obtain a workpiece of the desired shape and size. This process is like a blacksmith forging iron; through repeated hammering, not only is the shape shaped, but the coarse grains inside the metal are broken down, the microstructure is refined, and microscopic defects are compressed, thus giving the material its initial foundation of strength and toughness.

2. Why Do Forgings Need Tempering?

However, untreated forgings are like uncarved jade, their performance far from optimal. They typically face a dilemma:

State A (after quenching): High hardness and strength, but too brittle, like glass, easily broken by impact.

State B (after annealing): Soft and tough, but too soft, insufficient strength, easily deformed.

For many critical parts subjected to complex alternating loads and impacts (such as automotive connecting rods, machine tool spindles, etc.), we want them to be both hard enough (high strength) to resist deformation and flexible enough (high toughness) to absorb impact energy without breaking.

Temperature treatment was developed to perfectly resolve this contradiction.

II. The Two Steps of Tempering: Quenching + High-Temperature Tempering

1. Step 1: Quenching – The “Ice-Sealing” Magic of Rapid Cooling

Process: The forging is heated above its critical temperature (usually 850-950℃), causing its internal structure to completely transform into a homogeneous state called austenite, and held at this temperature for a period of time to allow the carbon atoms to fully dissolve. Then, it is rapidly immersed in a cooling medium such as water, oil, or a polymer solution for rapid cooling.

Purpose: This rapid cooling prevents the normal diffusion of carbon atoms, forcing austenite to transform into an unstable, supersaturated solid solution – martensite. Martensite is extremely hard, but has enormous internal stress and is also very brittle. At this point, the forging is “unyielding,” in a state of extreme internal tension and instability.

Imagine plunging red-hot steel into water, much like immersing scorching glass in cold water for a “fire and ice tempering” process, instantly “freezing” its surface and interior to form a hard but brittle structure.

2. Step 2: High-Temperature Tempering – A Carefully Controlled “Decompression” Ritual

Process: The highly brittle forging after quenching is reheated to a relatively low temperature (typically 500-650℃), held for a sufficient time, and then slowly cooled to room temperature.

Purpose: This is the finishing touch of the entire tempering process. The tempering process provides energy and impetus to the unstable martensite, causing it to decompose:

Stress Relief: Releasing the enormous internal stress generated during quenching.

Microstructural Transformation: Supersaturated carbon precipitates as fine carbide particles, while the martensite itself transforms into a stable, tough tempered sorbite structure.

Final Result: Tempered sorbite is a mixed structure composed of a ferrite matrix and dispersed fine carbides. It retains the high strength of martensite while significantly improving the material’s plasticity and toughness due to its highly dispersed, fine structure.

It can be likened to this: a quenched forging is like an athlete with taut muscles, on the verge of collapse. High-temperature tempering, on the other hand, is like a scientific relaxation and massage, relieving the muscle tension (internal stress), adjusting its state, making it both strong (high strength) and flexible (high toughness), capable of handling various impacts (impact loads) in a competition.

III. Superior Performance Resulting from Quenching and Tempering

Forgings that have undergone quenching and tempering experience a qualitative leap in their comprehensive mechanical properties:

High Strength: Able to withstand enormous loads without permanent deformation.

High Toughness: When subjected to impact, it can absorb a large amount of energy through its own plastic deformation, avoiding catastrophic brittle fracture.

Good Fatigue Strength: For forgings subjected to stresses with periodically changing direction and magnitude (such as rotating shafts), the quenched and tempered structure effectively prevents the initiation and propagation of fatigue cracks, greatly extending service life.

In essence, tempering is the crucial step in giving steel its “soul,” transforming it from a “hard” material into a “living” and reliable component capable of bearing heavy responsibilities.

Temperature heat treatment, seemingly a rough process filled with fire and ice, is in fact an extremely precise science of materials. Through precise control of temperature and time parameters, it orchestrates a spectacular phase transition drama in the microscopic atomic world, ultimately endowing macroscopic forgings with exceptional vitality. The next time you witness those colossal machines operating steadily under immense pressure, you might recall that it is this balance between “quenching” and “tempering” that silently safeguards the backbone of modern industry